Table of Contents

Cider is a natural beverage produced from pressing and fermenting fruits such as apples. It can be alcoholic or non-alcoholic(apple cider).

The resulting juice can be consumed as a beverage or used as the base material in vinegar making. Depending on the type of fruit used, it varies in colour from pale yellow to dark amber, and its taste can be tart to very sweet.

One distinction needs to be made between using the word cider to describe the drink in North America and the rest of the world.

In North America, cider is usually associated with apple cider, which is unfiltered apple juice. In other parts of the world, when ordering cider, you will be served an alcoholic beverage. The equivalent of an alcoholic cider in North America is hard cider.

Non-alcoholic cider is made by pasteurizing and stopping the fermentation process, thus not allowing alcohol formation.

To make hard cider, the fermentation process is allowed to develop, which results in an alcoholic beverage.

England is the world’s largest cider producer by volume; other places with significant cider production are Argentina, Australia, Austria, Germany, Belgium, Canada, China, Finland, France (Normandy and Brittany), China, and the USA.

Cider alcohol content varies between 3% and 8.5%, but some ciders increase to 12%. In the UK, cider must contain at least 35% apple juice (fresh or from concentrate). In the United States, there is a 50% minimum. In France, Cider must be made solely from apples.

“An alcoholic beverage; fermented apple juice (in the UK may include no more than 25% pear juice). Dry cider has 2.6% sugars, 3.8% alcohol, and 110 kcal (460 kJ) per 300 mL.

A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition

Sweet cider has 4.3% sugars and supplies 125 kcal (525 kJ) per 300 mL.

Vintage cider has 7.3% sugars, 10.5% alcohol, and supplies 300 kcal (1260 kJ) per 300 mL (half pint).

History

Cider has been known to people for around 5000 years, as some archeological shards of evidence show.1

Cider was consumed not only in ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, which were the masters of cider-making, but also in the Middle East. Some evidence suggests that the Celts in Britain also used crab apples to make cider since 3000 BC.

After the Roman invasion of Britain in 55AD-43AD, they introduced apple cultivars and orchard techniques to England.

By the sixth century, the people in Europe had become skillful brewers2 of apple cider making, and later, somewhere around the X and XI centuries, we can see historical evidence of the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings drinking cider.

The Normans’ (Northmen) invasion of France, Spain, and southern England brought advanced pressing techniques and introduced more acidic apples.

However, the real change was in implementing the pressing technologies, which allowed for more efficient extraction of apple juice. 3

Initially, the orchards were seedlings; the trees were grown from seeds, which resulted in a mix of new and unknown apple varieties. All the apples in the orchard were collected and used to make cider, as some were too tart to eat.

To grow only the preferred apple, they used the grafting technique, which farmers have used since 50 BC, to graft popular apple cultivars onto the rootstock of another tree.

Apple producers started making clones of popular cultivars, which eventually gave different names to these apple varieties.

By the 1500s, Normandy had sixty-five different apples, and some of the most commonly used fruits in cider-making came from there. The Normandy region became one of the largest cider-making areas in the world. Farmers experimented with different apples and manufacturing, which was great for developing new ciders but led to inconsistent tasting experiences.

There were two different styles of making Cider: English and French.

• The English way. They used open fermentation vats and bittersweet crab apples, which gave the cider a drier taste and higher alcoholic content.

• French way. They developed sweet, low alcoholic cider, taking advantage of the sweeter apples and the keeving process, making a naturally sweet sparkling cider style. 4

Cider was a popular drink in America from the 18th to the late 19th century. According to legend, one of the people credited with it was John Chapman, aka Johnny Appleseed, who established nurseries from seeds and grew orchards in the Midwest.

Chapman moved from Pennsylvania to Illinois, acquired land, planted orchards and nurseries, and sold them to incoming pioneers for a profit. Most of the apples produced were too tart to eat, but usually suitable for cider, which led to increased production.

Another reason for drinking cider was the quality of the drinking water, which was usually contaminated with bacteria such as E. coli. It was safer to drink alcoholic cider; even kids were drinking it. Especially for kids, they made a special apple drink called Ciderkin, a weak alcoholic drink made from soaking apple pomace in water.

During Prohibition, cider production declined and didn’t recover much until the early 2000s, when some craft beer companies started producing and distributing cider on a larger scale.

Cider in Canada

The history of cider (hard cider) in Canada most likely began around the early 1600s; who exactly brought the cider-making to the shores is unclear. Was it the British or the French?

History tells us that around 1617, a few years after the French settlers founded Quebec, around 1608, Louis Hebert, an apothecary from France, planted the first apple tree. Most of the settlers were Normans who brought their cider-making traditions and set the beginning of orchard development in New France.

Around the same time, in the early 1600s and 1700s, French settlers in Nova Scotia planted apple trees, and settlers from Britain and Germany, known for their cider-making, arrived, which helped establish the cider-making traditions.

In the mid to late 17th century, Canada’s earliest cidery was established on Mont-Royal in New France by Sulpician priests who planted an orchard and erected a cider mill. 5 In 1731, the orchards covered 90 arpents (76.0 acres) on the Island of Montreal, and some of the common cultivars at the time were the Calville blanc, Calville rouge, Famous, Reinette, and Bourassa.

Until the late 1800s, cider was one of the most popular drinks, but with the advancement of beer making, it was slowly replaced as a go-to drink, and the cider industry as a whole came to a halt.

The Temperance movement and Prohibition put more pressure on cider-making but contributed to the creation and production of non-alcoholic apple cider.

It took nearly 100 years to recover the cider, mainly through craft cider production. Here is Euromonitor’s cider outlook projection for selected markets.

*CAGR: Compound annual growth rate

agr.gc.ca

According to the Canadian Food and Drug Regulations, Cider in Canada is “an alcoholic cider that is an alcoholic fermentation of apple juice that does not contain more than 13% absolute alcohol by volume (ABV) or less than 2.5% ABV.”

How Cider is Made

With time, cider-making techniques were refined and standardized, cider production technology improved, and people now understood the steps needed before the product was ready to be shipped to retailers.

Raw Material

Apples are the most common material for making cider; pears and cherries are also used, but not to the same extent. The type of apples used determines the predominant flavour of the final product.

Ciders can be classified differently, but generally range from dry to sweet.

The preferred apple cultivars for dry cider making are the more acidic tart varieties, McIntosh, Pink Lady, and crab apples, and the sweeter ones are used in varieties like Fuji and Gala.

The most suitable ones are called cider apples, and manufacturers use them to make cider. Here are some examples.

| Common name | Origin | First developed |

|---|---|---|

| Baldwin | Wilmington, Massachusetts, US | c. 1740 |

| Brown Snout | Herefordshire, England | c. 1850 |

| Dabinett | Somerset, England | late 19th century |

| Dymock Red | Gloucestershire, England | |

| Ellis Bitter | Newton St. Cyres, Devon, England | c. 1850 |

Classification of Apples for Cider Making

- Sweet: Low tannin, low acidity (Golden Delicious, Binet Rouge, Wickson)

- Sharp: Low tannin, higher acidity (Granny Smith, Brown’s, Golden Harvey)

- Bitter sharp: Higher tannin, higher (Kingston Black, Stoke Red, Foxwhelp)

- Bittersweet: Higher tannin, lower acidity (Royal Jersey, Dabinett, Muscadet de Dieppe)

- In France, the cider varieties are classified into five groups:

- sweet (Clos-Renaux)

- Bittersweet (Bisquet)

- bitter (Cidor),

- acid (Judeline)

- Sour (Juliana)

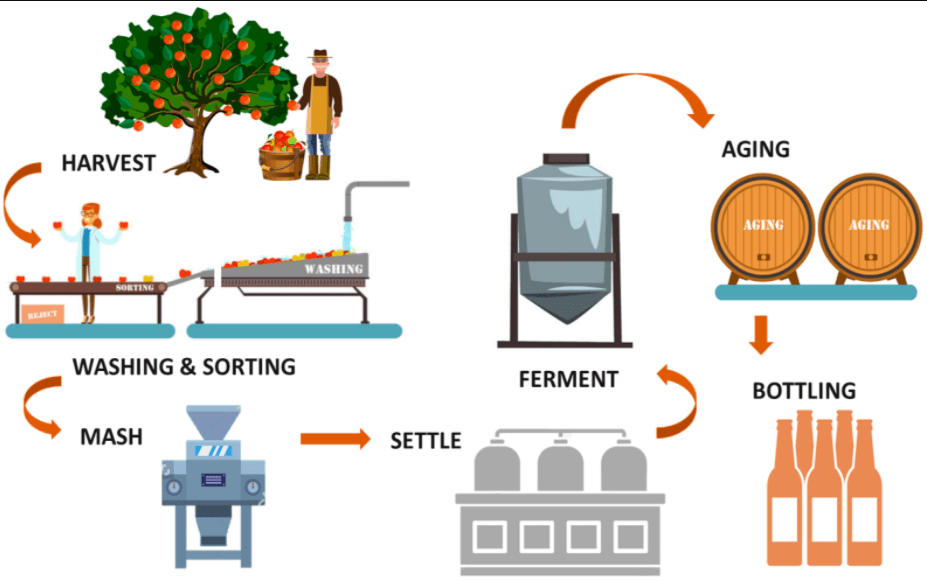

Steps involved in cider-making

researchgate.net – (CC by) license – 4.0

Harvest, “sweating,” washing, grinding, pressing, blending, testing, fermentation, racking off, filtering or fining, bottling, and storage.

Harvesting

The harvesting process usually occurs in the Fall, depending on the location. Only good quality ripe apples are used, occasionally green for added acidity, and certainly not the rotten ones to be mixed with the good ones.

After harvesting, the product is brought to manufacturing facilities, undergoing sweating.

Sweating process

Apples are stored on a concrete or wooden platform for about a week to ten days until they soften up and are ready for grinding.

The reason for the sweating process is to:

-Increase the sugar in the juice

-Makes the fruit easy to grind

-Allow full flavour to develop

Note: Some varieties, Rome Beauty and Newtown, don’t undergo this process; they can be freshly picked and pressed.

Washing

Apples have to be washed well. The purpose of washing is to remove dirt, harmful bacteria, and any chemicals being sprayed on. They go through the scrubber from the bins, onto a conveyor, and into a hopper filled with water for washing. After that, they return to a conveyor, are sprayed again with water, and are inspected. Rotten apples that are not up to the producer’s standards are removed.

Grinding

The apples are sorted and blended based on the cider type before grinding and pressing.

The blending stages can be done at any of the following steps:

1) Before grinding

2) Before fermentation – after pressing

3) After fermentation, blending at this step gives the most excellent control over the quality of the finished cider.

A typical blend of apples might include approximately 50% sweet, 35% acidic, and 5% astringent. National Honey Board 2003).

The fruit should be ground to a fine pulp to extract the maximum juice. Apples may be ground whole, including cores and skin, to a fine pulp with the consistency of applesauce. This ensures the maximum amount of juice can be extracted from the apples. The finer the pulp, the greater the yield of juice.

Also, the grinding has the added benefit of reducing damage caused by oxidation.

The pulp is separated from the juice, and some is frozen for later use, if needed, to produce more cider.

Pressing

The pulp(pomace) is pressed in wooden forms lined with nylon to remove the juice. Based on the type of press used, the pulp may be dumped onto press cloths, which are folded over and built up in many layers within a series of racks. The applied hydrophilic force can deliver as much as 30,000 lbs of pressure.

As pressure is applied, the juice flows out. The pressing time varies; for instance, it can take overnight at home.

The juice’s contact with the air triggers the oxidation process, which gives the cider a darker colour.

The juice should not be exposed to air or insects but funnelled into fermentation containers as soon as the pressing is over.

After this step in commercial production, SO2 oxide and 10% water are typically recommended. One reason SO2 is added is to prevent the growth of contaminating microorganisms. It is also essential to measure the pH level, which has to be lower than 3.8; if it is higher, malic acid is added to reduce it.

Cooling

Before cooling, the juice is run through a fine mesh to remove any small pulp particles. Then, it is moved through plastic pipes into cooling tanks and chilled to temperatures close to 0°C to remove any remaining harmful bacteria.

Testing

Sugar and acid levels are critical in cider. The amount of sugar in the juice will tell us the alcoholic strength of the final product, and the acid level should also drop.

Fermentation

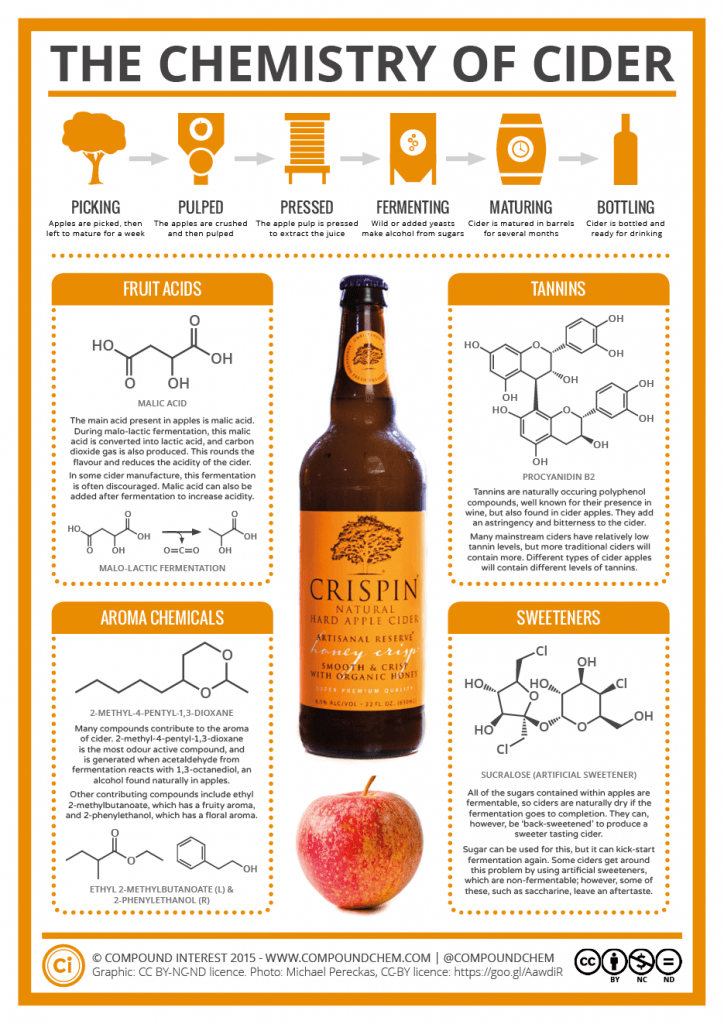

The conversion of simple sugars characterizes the process of alcoholic fermentation into ethanol by yeasts.

Sugar is converted to alcohol during fermentation; the higher the sugar levels in the juice, the higher the alcohol content. The acid level should drop during that process, but if the juice is contaminated with Acetobacter, acetic acid (vinegar) is produced.

The sugar and acidity levels are also essential to the amount of alcohol and acidity in the final product.

One significant difference in cider fermentation occurs at a lower than usual temperature (4°-16°C), and the reason is to preserve the extraction of more delicate flavours, but at the same time, that leads to an increase in the length of the fermentation.

Depending on the manufacturer, the cider may ferment in a large, sealed bulk tank or individual bottles.

Natural cider fermentation can occur using wild yeast present in the must, or some producers choose to use cultures created by them.

It works because the yeast flora is “fed” by natural sugars, resulting in two by-products: alcohol and carbon dioxide (CO2).

Fermentation slows and stops when sugar is no longer available for yeast.

“Since 1980s, use of active dried wine yeast has been widespread. The temperature is likely to be within the range 15–25°C, where temperature control is affected”(Bamforth, 2014).

Malolactic fermentation – MLF

Malolactic fermentation is a process through which lactic acid bacteria (LAB) convert malic acid to lactic acid. The main impact of MLF on Cider is likely to be seen in deacidification, as malic acid is more potent than lactic acid. The conversion will increase pH and change the perception of acidity.

The process can create other compounds and change the flavour or aroma of the cider; notably, MLF can produce diacetyl well above the taste threshold and other compounds that may not be above the taste or aroma threshold but may increase perceived complexity.6

Apple-based juice may also be combined with fruit to make a fine cider; real fruit purees or flavourings like grape or cherry can be added.

The cider is ready to drink after a three-month fermentation period, although the maturation process can last up to three years.

The second fermentation, MLF (Malolactic fermentation), which converts malic acid to lactic acid, making it less acidic, can occur concurrently with yeast fermentation. Still, it is often delayed until a few months later.

Spontaneous Fermentation

Some areas of the world are seeing it make a comeback. Spontaneous fermentation of apple juice to cider is very easy. It requires no more effort than buying fresh-pressed, unpasteurized, and untreated (raw) apple juice and then forgetting about it for a few weeks or months.

There are two options for this type of fermentation:

- This typically takes longer in the fridge, resulting in a sweeter end product with a more pronounced apple flavour.

- At room temperature, this would proceed much like any normal fermentation, and due to the unknown nature of the microbes contained within, it is likely to dry out.

Wild Yeast Isolation

Check here for more information.

Keeping Fermentation

The traditional process is used in France to carbonate sweet cider naturally.

See this video on how it is done.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h3j-iQRnaes&t=1s

The timing of removing the yeast from the fermentation process will determine the type of final product one is after.

Most UK manufacturers produce dry, high alcohol content ciders – 10-12%; in that case, all the yeast has been used.

Suppose the yeast has been removed halfway through the fermentation. In that case, the hard cider made in the US, which has the usual alcohol content of 5.5%, will result in a lower alcohol content and more fermentable sugars.

Fermentation is also dependent on the temperature. The higher the temperature, the faster the fermentation.

Double fermented cider

Cider is initially fermented to a lower than typical alcohol content (e.g., 5% ABV) by restricting the total amount of sugar present. The liquor is racked off as soon as the cider is fermented to dry and either sterile-filtered or pasteurized before transferring to a second sterile fermentation vat.

Sugar and apple juice are added at that point of fermentation, and secondary fermentation is induced following inoculation with an alcohol-tolerant strain of Saccharomyces spp. Such a process permits the development of very complex flavours in the cider.

B. Jarvis, in the Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition (Second Edition), 2003

Chemical Reactions

Alcoholic fermentation can be described as a three-step process:

Phosphorylation breaks glucose and fructose (six-carbon molecules) into phosphoglyceraldehyde (three-carbon molecule).

Phosphoglyceraldehyde (a three-carbon molecule) is transformed into carbon acetaldehyde and carbon dioxide (a source of CO2 for fermentation) by decarboxylation.

Acetaldehyde is reduced to ethyl alcohol as an end product.

Racking off

After fermentation, racking is used to leave behind as much yeast as possible. Shortly before the fermentation consumes all the sugar, the liquor is “racked” (siphoned) into new vats, leaving dead yeast cells and other undesirable material at the bottom of the old vat. At this point, it becomes crucial to exclude airborne acetic bacteria.

Racking involves removing the newly fermented cider from its lees. The cider is drained into the second fermenting tank or bottles using a clean plastic tube.

Filtering

This step makes a cider crystal clear. This can be done by implementing these two methods:

- Using a closed filter system to avoid exposing the cider to air (risk of acetic bacteria contamination)

- Mix gelatin, bentonite, and a pectic enzyme into the cider.

Bottling

First and foremost, the bottles need to be sterilized. For an “in-bottle fermentation,” a small amount of sugar may be added to each bottle. During pasteurization, a small amount of sulphur is added to prevent the yeast from dying after introducing the sugar.

The best ciders are made from 100% freshly pressed apple juice, fermented slowly for months, and then aged, often in oak barrels, for months, but that is not always the case. In the UK, for example, the minimum amount of apple juice is 35%; in the US, it is 50%; the rest is water. Which one tastes better? I guess it is up to the consumers.

Storage

The bottles should be kept in a cool, dark place. They can also be kept in the fridge, but not in the freezer.

“Cider should best be served chilled — not warm, and not ice-cold.” If it’s too cold the flavor is masked. … You want it to be refreshing on a hot day, but if you do want to get the full flavor, a temperature of around 46–50°F is perfect.”

Bradshaw and Brown: World’s Best Ciders: Taste, Tradition, and Terroir

Types

Cider comes in various styles: still, naturally sparkling, bottle-fermented, method champenoise, carbonated, dry, medium, sweet, ice cider, cider brandy, acidic, tannic, and wild yeast fermentation.

Vintage and Single Cultivar Ciders

Vintage ciders are made only from fresh juice from a named year. Some vintage and other ciders are made from a single apple cultivar’s juice.

Modern Cider7

Modern ciders are generally made primarily from culinary or table apples. Compared to other Standard styles, these ciders are usually lower in tannin and higher in acidity.

- Dry ciders will be more wine-like with some esters.

- The flavour of Sweet or Low-alcohol ciders may have an apple aroma and flavour.

- Sugar and acidity should combine to give a refreshing character.

- Acidity is medium to high, refreshing, but must not be harsh.

- The colour is brilliant, from pale to gold.

Heritage Cider

Heritage Ciders are made primarily from multi-use or cider-specific bittersweet/bitter, sharp apples, with wild or crab apples sometimes used for acidity/tannin balance.

These ciders will generally be higher in tannin than Modern Ciders. These ciders typically lack the malolactic fermentation (MLF) flavour notes often found in Traditional Ciders from England or France.

- Aroma/Flavour: Sweet or low-alcohol ciders may have an apple aroma and flavour.

- Dry ciders will be more wine-like with some esters.

- Sugar and acidity should combine to give a refreshing character.

- Acidity is medium to high, refreshing, but must not be harsh.

- Appearance: Clear to brilliant, yellow to gold in colour.

Traditional Cider – England and France

Most ciders in England are dry and use malolactic fermentation (MLF), producing desirable spicy/smoky and farmy characters.

The one made in France is sweet, with typically sweet and balanced tannin levels, and is made from the traditional apple varieties.

Medium to sweet, full-bodied, and rich. Carbonation is moderate to champagne-like.

Sour Cider

Sour ciders include those produced in Northern Spain (notably Asturias and the Basque Country).

Aroma: Ciders from Asturias typically have fresh citric and floral aromas.

They have a unique traditional serving method.

The bottle is held in one hand, with the arm reaching as high as possible. On the other hand, the glass is held at an angle, with the arm stretched down as low as possible. The cider is carefully poured so that a thin stream of liquid drops from a height into the tip of the glass. Only a small amount of cider is poured, just enough to consume in a mouthful or two. The aim is to release carbon dioxide in the cider and to volatilize part of the acetic acid.

Fruit Cider

Fruit cider has added other fruits or fruit juices, including berries, quince, rhubarb, and pumpkin.

Hopped Cider

Hopped Ciders are ciders with added hops.

Spiced Cider

Spiced cider has added spices like “apple pie” (cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice).

Wood-Aged Cider

Wood-fermented or wood-aged ciders in which the wood/barrel character, or the liquid previously stored in the barrel, is a notable part of the overall flavour profile. Tubes, chips, spirals, staves, and other alternatives may be used instead of barrels.

Ice Cider

Ice Cider is a style that originated in Quebec in the 1990s. Juice is concentrated before fermentation, either by freezing the fruit before pressing it or freezing the liquid and removing water as it thaws. The fermentation stops or is arrested before the cider reaches dryness. No additives are permitted in this style; in particular, sweeteners may not be used to increase gravity.

It differs from an apple wine cider in that the ice cider process increases the sugar (hence alcohol), acidity, and all fruit flavour components proportionately.

Sparkling Ciders

Sparkling cider is generally carbonated to a 3.5–4 bar pressure level and bottled in champagne-style bottles with wired closures.

The product is usually sterile-filtered before bottling. Traditionally, sparkling cider received a secondary ‘in-bottle’ yeast fermentation (méthode champanoise), but such processing is rarely seen nowadays.

Sometimes, a process called cuvée close is used. Secondary yeast fermentation is done within a sealed tank, developing natural carbonation in the cider before bottling.

Under EU legislation, it is illegal to refer to sparkling ciders as ‘champagne cider.’

White Cider

White Cider is prepared by fermenting decolorized apple juice. The fermented cider is decolorized by treatment with activated charcoal or other suitable decolorizing agents (e.g., PVPP) before final blending. ‘white’ indicates that the product has little or no colour.

De-alcoholized and Low-Alcohol Ciders8

De-alcoholized ciders are prepared by removing the alcohol from the strong cider using thermal evaporation, reverse osmosis, or other suitable technology to give a product with an alcohol content not above 0.5% ABV. De-alcoholized cider lacks body and flavour and is not sold commercially.

Low-alcohol cider (< 1.2% ABV)

Low-alcohol cider is prepared by stopping fermentation or fortifying de-alcoholized cider with apple juice or other ingredients to provide a product with a flavour and aroma similar to regular alcoholic cider.

Organic Cider

In Europe, some cider makers offer cider made only from fruit grown following EU Regulations governing organic horticultural practices.

The fruit is pressed separately from non-organic fruit and can be treated only with gaseous sulphur dioxide. Other ingredients included in the product must also conform to current legislation on organic products.

Modern Perry

Modern Perry is made from culinary/table pears. It tends toward that of a young white wine.

Traditional Perry

Traditional Perry is made from pears grown specifically for that purpose rather than for eating or cooking.

Apple cider – Non-Alcoholic

CC BY-SA 3.0

apple cider (left) and apple juice

unfiltered and filtered-pasteurized

Apple cider is used in the United States as an unfiltered, unsweetened, non-alcoholic beverage made from apples.

In Canada, apple cider refers to the non-alcoholic version, and cider is the alcoholic one.

According to the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, there is no apparent difference between apple juice and apple cider.

“apple juice and apple cider are both fruit beverages made from apples, but there is a difference between the two. Fresh cider is raw apple juice that has not undergone a filtration process to remove coarse particles from pulp or sediment. Apple juice is the juice that has been filtered to remove solids and pasteurized so that it will stay fresh longer. Vacuum sealing and a

additional filtering extends the shelf life of the juice.”

Canada recognizes unfiltered, unsweetened apple juice as cider, fresh or not.

Recipes

Homemade recipe – Cider (French Traditional Recipe FOR 1 L)

Ingredients:

French countryside recipe from Science Direct – 4.5.1 Apple Wine (Cider)

6 kg ripped apples

0.2 L water

200 g + 1.1 kg sugar

1 kg yeast nutrient

Chop the apples and boil them in water with 200 g sugar and the yeast nutrient added. After cooling, press, and in the obtained juice, add gradually (during 2–3 days) 1.1 kg of sugar in three doses and allow for fermentation. After starting to clarify, under sulfating, rack the wine and bottle.

Cider Cup

The cup is a part of the drink families; it originated around the mid-1800s. It is usually made with spirits, wine, cordial or vermouth, fruits, and sugar. Cider Cup has many recipes; some are for individual drinks, others for larger parties.

This particular recipe is from John Applegreen’s book “Barkeeper’s Guide or How to Mix Drinks” – revised edition, p30, 1904

Use a large glass pitcher into which to put

1 lemon, sliced

1 orange

2 pieces cucumber rind

1 pony brandy

I pony a white Curacao

1 1/2 quart champagne cider or sweet cider as preferred

The juice of one lemon

1 large piece of ice.

Stir well and decorate with a small bunch of green mint. Serve in medium sized tumblers.

Footnotes

- DAVID A. BENDER “cider .” Dictionary of Food and Nutrition https://www.encyclopedia.com.

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/sports-and-everyday-life/food-and-drink/alcoholic-beverages/cider#:~:text=Archaeological%20evidence %20shows%20that%20ancient,factors%20that%20impact%20cider%20flavor cider.

- https://www.utne.com/arts/history-of-cider-making-ze0z1306zpit#:~:text=The%20Greeks%20and%20Romans%20mastered,established%20across%20E…https://www.utne.com/arts/history-of-cider-making

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cider#Geography_and_origins Origins

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadas-craft-cider-revival Thecanadianencyclopedia.

- CiderMalolactic_Fermentation Milkthefunk.com/wiki.

- Winecompetitions https://www.winecompetitions.com/ciderstyles

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/food-science/cider#:~:text=4.5.,cider%20goes%20to%2012%25%20alcohol ScienceDirect.