Table of Contents

The post on coffee flavours and temperature influence is not about how to drink coffee or tea. It is more about getting out of your comfort zone, experiencing and enjoying the coffee’s perceived flavour nuances, or any drink, for that matter, served at different temperatures.

Much information discusses the “ideal” and “perfect” coffee serving temperature and many other drinks. Still, the correct answer for me is a straightforward rule.

The right serving temperatures are the ones you feel are the most enjoyable while consuming any drink, and that subjectivity actually is the reason that creates the problem of defining what these “ideal” temperatures might be.

Unless one makes a beverage for consumption, it will be virtually impossible to please everyone due to a lack of objective criteria defining the highly subjective taste and aroma preferences.

Of course, we can use the sum of averages, gender preferences, statistic results based on lab test experiments, or customer feedback. However, we will still define these temperatures based on the majority, not the absolute one hundred percent agreement from our customers, friends, or volunteer taste subjects.

That automatically eliminates the words “perfect” or “ideal” as being part of the definition of what the hot/cold temperatures should be and introduces the more inclusive one “suggested.”

The “ideal/recommended” serving temperatures will always represent the majority of people’s expectations and are closely related to their psychological flavour perceptions.

While making or serving drinks, we all try to manage someone else’s expectations. If we don’t meet that minimum goal, we will have many disappointed people, and if we run a business, we will have a tough time ahead of us.

For the minority, serving flexibility and accommodation come into play. Again, if we are a business, we can have a section on the menu offering coffee, tea, beer, wine, or liquor at different temperatures than the industry-recommended ones.

Since there is no such thing as perfect serving temperatures, one might ask, “What is the point of trying to define something so subjective when it is clear that we will never be able to achieve 100 percent accuracy?”

There are two possible answers to this question.

- Serve the drinks based on the accumulated experience of customer feedback you collected over the years, and don’t bother with any suggested or “ideal” temperatures; it is an easy way of keep doing what you are doing, and it saves time and effort of learning something new, but at the same preventing you from offering new experiences to your customers or friends.

- The second option will be to focus on the benefits for your clientele and business if you explore the different serving temperatures.

Option one is straightforward: do what you’ve been doing and serve the drinks according to industry recommendations and clientele feedback.

Option two explores how different temperatures influence the flavour of the drinks and their effect on customer experience. It looks at the possibility of another way of serving drinks, allowing you to experiment and hopefully provide unique and different sensory experiences to your patrons or friends.

I’ve always been interested in discovering why and how flavours significantly influence human behaviour. The corresponding answers may or may not always lead to different actions.

One thing is for sure: the road to learning and understanding what is happening in our beverage and how we perceive the taste under different temperatures will benefit our quest to become better in the craft of bartending.

Taste and Temperatures

What is taste, and how do we define it?

While drinking or eating, we constantly assess the quality and personal satisfaction of the products we consume. The usual outcome of this process sounds like “It tastes like…”. The word taste has become an everyday expression/substitute for flavour.

The taste is only one part of the flavour perception; it is identified by its qualities such as:

- sweet – reflecting the presence of carbohydrates/sugars

- sour – acidity

- salty – sodium and minerals content

- bitter – potential toxins

- Umami/savoury – glutamates and other amino acids, present in seaweed, meat broths, and fermented products, indicate protein.

- Fat – more mouthfeel than flavour.

- Astringency is similar to fat in that it is more feeling than taste.

Each one detects different nutritional components in food or beverages1.

The last two qualities are not officially recognized yet as taste, but there is considerable evidence of their taste sensations.

- Fat – a fatty acid transporter CD36 is found in the oral cavity on human taste buds, and a decreased sensitivity to fat taste is also associated with increased fat consumption.

- Aristotle classified the fat sensation as a taste as early as 330 BC and later in a 1531 AD text on physiology by Jean François Fernel. More recently, fat has been associated with texture, flavour release, and thermal properties in foods but not with the sense of taste2.

- Astringency – tannins in tea or red wine can cause this sensation, usually as roughness on the tongue. Imagine forgetting a tea bag in tea for a long time and then having a sip.

The primary organ responsible for taste is the tongue. It contains taste receptors that identify non-volatile chemicals in foods and beverages, allowing us to determine their taste qualities.

It has to be mentioned here also that taste is hardwired with our brains, we are born with it, as opposed to smell recognition, which can be learned over time. The main purpose of the taste is to protect us from any food/drinks that potentially can be harmful, and It has evolved as a vital survival mechanism in mammals. Think of it as a gatekeeper, sweet might be good, but bitter or sour may signal spoiled food.

Additional flavour receptors

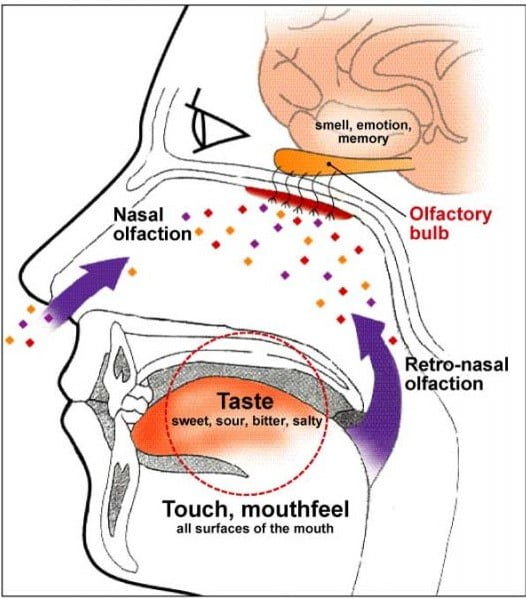

As I mentioned before, taste is only one of the contributors to the perceived flavour; the other parts are touch-mouthfeel, smell, vision, and sound. Each plays a vital role in providing the necessary information to our brain, where all the decisions on whether we like or dislike a particular food or drink are made.

Other variables also influence a particular flavour decision; they are triggered lots of time on a sub-conscience level and influenced by memories, past experiences, mood, ambiance, and cultural background.

Touch – Mouthfeel

The “feel” of a food or beverage, produced by mechanical stimulation and mediated by the tactile sense (the sense of pressure, traction, and touch), is an essential but often overlooked flavour aspect.

The touch system tells us that a substance (food or drink) is in our mouth and triggers the taste (the gatekeeper) to inspect that substance. The results are sent to the brain, where a decision is made on whether the substance is safe to be ingested.

Once we get the go-ahead that the food or drink is safe, the touch/motor system is activated again. We break down the food in our mouth or, for liquids like wine, swishing it around slowly with the tongue and exposing it to the taste buds.

Smell

Our sense of smell is responsible for about 80% of our taste. Without our sense of smell, our taste is limited to only five distinct sensations: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami. The smell is two senses combined in one;

- Orthonasal olfaction – a smell through our nose while we breed in and sniff a particular substance.

- Retronasal olfaction is a sense of smell triggered by breading out. It occurs in the mouth and contributes to the flavour of foods or drinks. Retronasal olfaction is commonly associated with the sense of taste as it is closely fused with taste and touch.

In the case of drinking wine, we are swishing a sip of wine in our mouth, and at the same time, we are breathing out, causing the volatile molecules to exhale and create a flavour sensation.

The retronasal smell is fascinating in that we often think of it as taste, and it is the reason for expressions like “it tastes like lilacs, grass, or any other aroma.” That’s impossible, as taste is usually associated only with sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami.

Next time you have food or drink, try not to breathe out immediately; make sure you are doing it safely, and then eat or drink slowly to feel the difference in flavour release and enjoyment.

Vision

It has a significant influence on how we perceive the flavour. It often forms our perception of it even before trying it. As a bartender, I made numerous drinks based on the simple request, “I want to have the same drink as the person over there is having,” an order based only on the drink’s appearance without even knowing its ingredients.

Vision sense is about the food or drink’s appearance and the ambiance, whether clean, cozy, comfortable, bright, dark, etc. All these sensory inputs are instantly connected to our memory banks and related to previous experiences, good or bad, which leads to the most likely internal decision of “I like being here, or I’d rather spend my money somewhere else.”

Advertisers, for instance, are very well-versed in creating visual cues and promoting products in the most enticing possible way.

Sound

The sound is related to the texture of food, drink, and our surroundings. The sound of crunchy food, a clean pour of wine and beer, or a noisy/distracting background adds dimension to the flavour feedback.

Temperatures

Temperatures play an essential role in intensifying or masking aromas and taste qualities. Higher temperatures increase the perceived bitterness in beer and coffee, and lower temperatures can eliminate or reduce scents in drinks such as cognac, rakia, or grappa to a minimum.

These are just a few examples of flavour manipulation; whether these changes are desirable is not essential, as the decisions are based on personal preferences. The more important result is using different serving temperatures to experience new flavours.

Let’s use coffee as an example of a beverage equally enjoyable served hot and cold and try to answer a few questions;

1. What is the suggested brewing and serving temperature?

2. Does lower temperatures reveal or enhance any additional aromas? Not perceived otherwise.

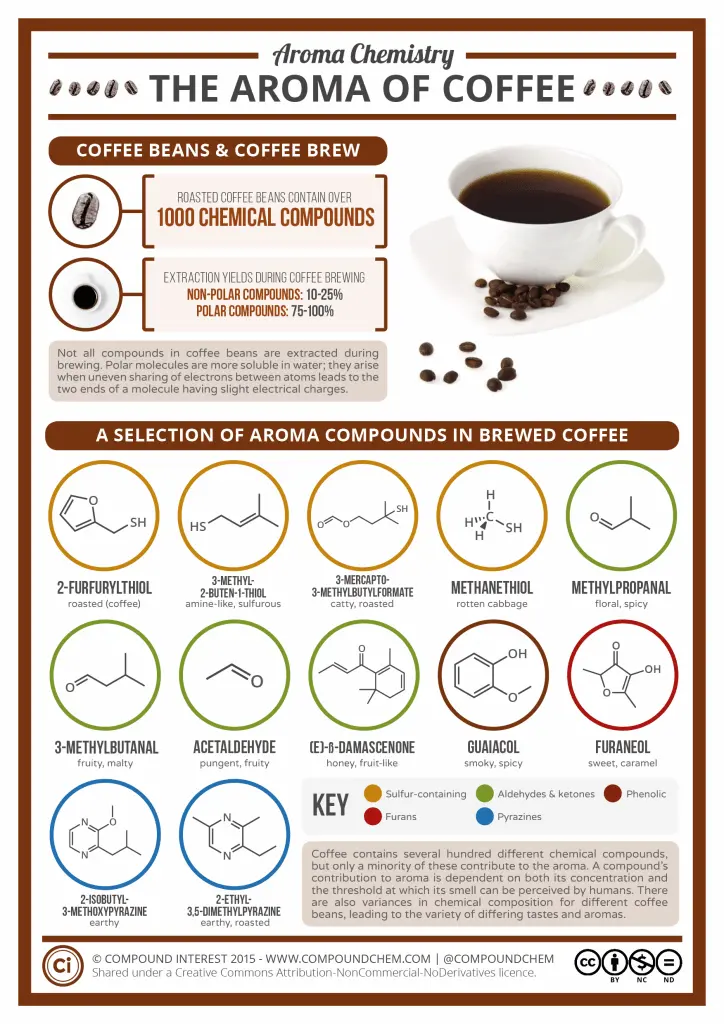

| Coffee chemical composition is a complex blend of more than 1000 chemical components, of which about 40 are responsible for the prominent coffee flavour. |

Before roasting, the green coffee beans have a slight aroma but are loaded with chemical compounds waiting to be extracted and enjoyed later.

The development of these aromas begins with the roasting process, where the different temperatures release specific aromas related to and associated with particular toast levels.

“The impact of roasting on taste comes from the degradation and formation or release of various chemical compounds through the Maillard reaction, Strecker degradation, decomposition of amino acids, quinic acids and lipids.”3

After the roasting and production cycle is complete, it is time to enjoy the delicious flavour of coffee, which leads us to the next important step- brewing.

According to the National Coffee Association, the suggested brewing temperature uses water between 195 and 205 degrees Fahrenheit for optimal extraction. This is not to be confused with serving one, which is much lower than that.

Brewing water temperatures for teas are lower than that, and it also depends on the type of tea.

We need a higher brewing temperature to extract fuller flavour profiles, and we also have to factor in a few more variables.

- Different temperatures extract different chemical compounds.

- Type of roast being used. The optimal water temperature for darker roasts is around 185 degrees Fahrenheit, as the boiling water may extract some burn/ash aromas.

- Coffee brewing methods.

Serving Temperatures

Numerous studies have been done on consumers’ preferred hot beverage serving temperatures, and all share one thing. The desirable and safer range is between 130 to 160 °F (54.4 – 71.1°C).

For coffee brewing, hot water was passed over coffee grounds into a carafe, which decreased the temperature from 3 °C (∼5 °F) for insulated carafes to about seven °C (20°F) for uninsulated carafes; the range was also dependent on the type of brewing equipment.

At that point, the coffee temperature drops approx. 10-15°C (20 to 25 °F) in the in-room environment in 5 minutes. That time doubles if the carafe has a cap on it, which brings it to the taste within the preferred temperature range of 130 to 160 °F (54.4 – 71.1°C).

The studies were done using black coffee, and the preferred temperatures in the table were according to the volunteers’ taste preferences.

Preferred temperatures are based on the different studies.

| Borchgrevink et al. (1999) | 68.3 °C (155 °F) |

| Pipatsattayanuwong et al. (2001) | 71.4 °C (161.8 °F) |

| Lee and Mahoney (2002) | 59.8 °C (139.6 °F) |

| Brown and Diller (2008) | 57.8 °C (136 °F). |

| Stokes et al. (2016) | 70.8 °C (159.4 °F) |

| Dirler et al. (2018) | 63 °C (145 °F) |

Combined Recommended Coffee and Tea brewing/serving temperatures.

Perceived coffee flavours under different temperatures

According to the National Coffee Association, the recommended coffee serving temperatures were between 180-185°F. The recommendation has been removed from their website. It is recommended to be mindful and careful of the coffee temperatures being served and enjoyed.

| 82-85°C (180-5°F) | You must be careful with these temperatures above the pain threshold as they may scald the tongue. The predominant sensation is a lot of aromas and a burning feeling. At that time, the brain sends a signal based on the taste buds’ feedback to sip just a little bit and be careful. The olfactory center is not receiving enough information due to the small liquid in the mouth. The taste buds and the retronasal smell do not fully detect many coffee flavours. Therefore, they are not passed to our sensory system. |

| 65-79°C (155-75F) | Besides the 40C, the predominant taste notes are floral, fruity, nutty, and acidic. They are sensed through the taste, mouthfeel, and retronasal smell channels, compensating for the lack of intense aroma due to lower coffee temperature. |

| 48-65°C (140-170°F) | Besides the 40C, the predominant taste notes are floral, fruity, nutty, and acidic. They are sensed through the taste, mouthfeel, and retronasal smell channel, compensating for the lack of intense aroma due to lower coffee temperature. |

| 40°C(104°F) | Besides the 40C, the predominant taste notes are floral, fruity, nutty, and acidic. They are sensed through the channel of taste, mouthfeel, and retronasal smell channels, compensating for the lack of intense aroma due to lower coffee temperature. |

These coffee flavour profiles are guidelines for what one may expect at a certain temperature level. Thankfully, they are not written in stone. They depend highly on the coffee origin, type, level of roasting, water, brewing, and, most importantly, the human element. We judge what we taste; our perceptions are uniquely individual and depend on our brain’s olfactory system to interpret the flavour we experience.

According to Karel Talavera Pérez, professor of molecular and cellular medicine at the University of Leuven in Belgium, studies recording the electrical activity of taste nerves demonstrate that,

“The perception of taste decreases when the temperature rises beyond 35C”.

When the temperature goes higher, we tend to taste less and less. The higher temperature triggers the cautionary safety signal, warning us of potential burning and overpowering the other taste-perceived receptors.

That also explains why some beverages, to appreciate their flavour profile fully, are best tasted at room temperature. The same applies if the temperatures are close to zero or below; the strength of the coffee aromatics will be diminished.

There is a difference between tasting and drinking on a side note here.

- Tasting is per suggested temperatures under which a complete flavour profile can be perceived.

- Drinking – There are no rules; have your drink according to how you enjoy it most.

Tasting notes are a collective effort/collaboration to describe a product’s flavour to someone who hasn’t tasted it yet.

Flavour perception is a fascinating topic. It involves forming flavour images, acting upon them, and exploring our decisions about what we eat or drink.

Suggested drink serving temperatures

Using serving temperature, one can manipulate the flavour of a drink. The general rule of thumb is that the higher the temperature, the more robust the flavour is perceived, but the most affected part of the smell, especially the Orthonasal part (the smell we detect through the nose).

Many manufacturers and advertising companies know this; the colder the drink, the less aroma is perceived, and more of the particular beverage can be consumed. Beer and brandy are two examples of that practice.

If one has a subzero-served beer, especially brandy, one will notice that most of the aroma is gone. By eliminating the smell, new potential customers who didn’t like the beer or brandy aromas can be attracted to try these products and thus increase sales.

I’m not saying this is bad or good; it is just another experience. I tried Remy Marten VSOP, which was served at subzero temperature. I enjoyed it; it tasted like chocolate with a long-lasting aftertaste, was easy to drink, did not have much aroma, and was perfect for people who don’t like cognac.

| Beverages | Suggested Serving Temperature |

|---|---|

| Water | 55F – 12.5°C |

| Sparkling water | 60F – 15.5°C |

| Lager | 42-48°F (5.5-8.5°C) |

| North American macro beers | 38-42 °F (0.5-4°C) |

| Pale ales, English pale ale | 42-50°F (7-10°C) |

| Ales | 44-52°F (7-12°C) |

| Belgium ales | 50°F – 10°C |

| Stout, Porters, Brown Ales | 50-55°F (10-12.5°C) |

| Barrel-aged beer | served at room temperature |

| Light white wines | 38–45°F / 3-7°C |

| Full-bodied white/Rose wines | 44–55°F / 7-12°C |

| Sparkling wines | 38–45°F / 3-7°C |

| Light red wines | 55–60°F / 12-15°C |

| Full-bodied red wines | 60–68°F / 15-20°C |

| Fortified wines | 60-65°F depends on the style |

Footnotes

- https://flavourjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2044-7248-4-5

- http://www.australasianscience.com.au/article/issue-january-and-february-2012/taste-fat.html

- Satrijo Saloko, Yeni Sulastri, Murad, and Mira Amalia Rinjani,

“The effects of temperature and roasting time on the quality of ground Robusta coffee (Coffea robusta) using Gene Café roaster,” AIP Conference Proceedings 2199, 060001 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5141310