Table of Contents

Whether the wine aroma and taste exist might seem as strange a question as it gets, but is it?

While having our glass of wine or any other drink, we focus on having a good time, relaxing, and enjoying the subtle aroma and smooth taste of our “perfect” glass of wine. It seems time has stopped; it is just you and the wine.

But what about people who lost their smell and taste abilities due to an accident, illness, or other reason?

According to Duncan Boak, the founder of the Fifth Sense, a charity for people affected by the loss of smell and taste,9

“It’s so hard to explain, but losing your sense of smell leaves you feeling like a spectator in yor own life as if you’re watching from behind a pane of glass, It makes you feel not fully immersed in the world around you and sucks away a lot of the color of life. It’s isolating and lonely.

It’s all gone. I feel that I don’t form memories in the same way – I don’t remember places I’ve visited that well, even if I’ve really enjoyed them…it’s very difficult.

@DuncanBoak

Many people have experienced a complete loss of smell, anosmia, loss of taste, and ageusia. It affects the perception of flavours, memories, and whole life experiences. People’s aroma and flavour have also been affected by Covid 19 to the point that food or drink has terrible or no taste.

In the case of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, researchers from NYU Grossman School of Medicine and Columbia University have discovered a mechanism that may explain why people lose their sense of smell. The virus indirectly reduces the action of olfactory receptors detecting the molecules associated with odours, leading to olfactory dysfunction in the ongoing reduction in the ability to smell (hyposmia) or changes in how a person perceives the same smell (parosmia).10

Losing these senses also has a far-reaching effect on our health; it is like losing the “gatekeepers” that prevent us from smelling or ingesting potentially harmful substances (poison, acid, gas leak, etc.).

Many people can regain some or all of their lost abilities with aroma training or treatment. Still, in that particular moment of no-sense abilities, the answer to whether a wine has flavour is pretty straightforward: No, it does not.

If some people can not detect odour and taste, does that mean the wine flavours are not in the base material but constructed by us and thus very subjective?

The sensory road of discovery

The discovery of flavours and perceptions is based on our sensory abilities and is formed in our brains. Smell and aroma are also found in the base material (grapes in the case of wine), but their sensory properties are chemical compounds.

When you eat or drink something, your taste buds pick up the chemical information and transmit it to the sensory processing centers, where the brain assembles and decodes it. Only then can we understand and decide on the flavour quality of the particular drink.

Decoding a flavour in our brain is not a simple math equation; its perception is influenced by chemical and physical interactions such as aroma recognition, taste, textures, sensations, vision, sound, and emotions.

To understand how everything is connected in our brain, let us look briefly at how the sensory inputs find their way into their respective processing centers and how that might help us appreciate and improve our wine-tasting experience.

I go into greater detail about flavour pathways and perceptions here.

When we are having or tasting wine, we are going through a few different steps;

- Visual inspection of wine, colour, and clarity.

- The sound of pouring

- Aroma – Orthonasal olfaction

- Secondary aromas – retronasal olfaction, breathing in and out, releases the retronasal smell.

- Taste – swishing around the wine in the mouth.

- Swallowing

- After taste – post swallowing.

All these steps contribute to our perception of the wine’s flavour and, based on our experience and knowledge or lack thereof, will determine our perception of the wine’s quality.

Vision

Vision significantly influences how we perceive wine flavour. We are already forming an opinion by looking at the colour, clarity, and sediments. The visual feedback triggers our imagination and creates expectations before even trying the wine, influencing the final evaluation. Implementing blind tasting will eliminate this factor.

Colour

The colour of the wine plays a significant part in determining the perception of aroma. Experiments showed how a liquid’s colour can deceive us into thinking of the smell it might have.

In 1972, Trygg Engen11, Professor of Psychology at Brown University for 36 years, conducted an experiment where two odourless solutions, one of them was coloured, were given to test subjects to rate their smell. The majority rated the coloured solution as having an odour.12 The test was performed only by sniffing (orthonasal smell).

2005 Deborah Zellner confirmed Professor Engen’s findings by conducting similar experiments. They presented the testers with two solutions: some had added smell stimuli, and some were colourless.

The results showed that the coloured one was perceived as having a more intense smell.

They did the same experiment again, but instead of sniffing, the researchers focused on the smell (retronasal) coming from the mouth after swallowing the liquid.

The results were the opposite of the previous taste. The colourless solution was categorized as more intense.

Both tests showed that the smell expectations of the tester could be influenced by colour, as the two parts of the smell are perceived differently 13 and how the initial perception can affect the retronasal smell and eventually the complete flavour image.

Testing was also done specifically on wine colour influence over the taster. One such test was done in 2001 by Morrot, Brochet, and Dubourdieu using white and red Bordeaux AOC wines.14

The wine comparison test was carried out by 54 undergraduates from the Faculty of Oenology of the University of Bordeaux. The sex ratio was 1:1. The wines used were Semillon and Sauvignon grapes for the white wine and Cabernet-sauvignon and Merlot grapes for the red wine. The test was conducted in two phases. In the first part, the student had to compare the flavours of the white and red wines, and for the second part of the test, the white wines were coloured with grape anthocyanin. The testers had to compare the white wines with coloured white wines.

The results showed that coloured wine was mistaken for red wine. In another test, blindfolded subjects, after tasting the same coloured wines, found no difference between the actual white wines and the coloured wines.

These wine experiments reinforced the idea that we are hugely influenced by colour, not just by wine but also by any other flavour object we are exposed to.

Hearing

The hearing sense input is related to the sound of pouring (“glou-glou”). A “glou-glou” wine (the term originated in the 17th century in France) or “glug-glug” in English is related to young wines meant to be enjoyed right away and not for storing.

Sensory path of smell and taste

Orthonasal smell

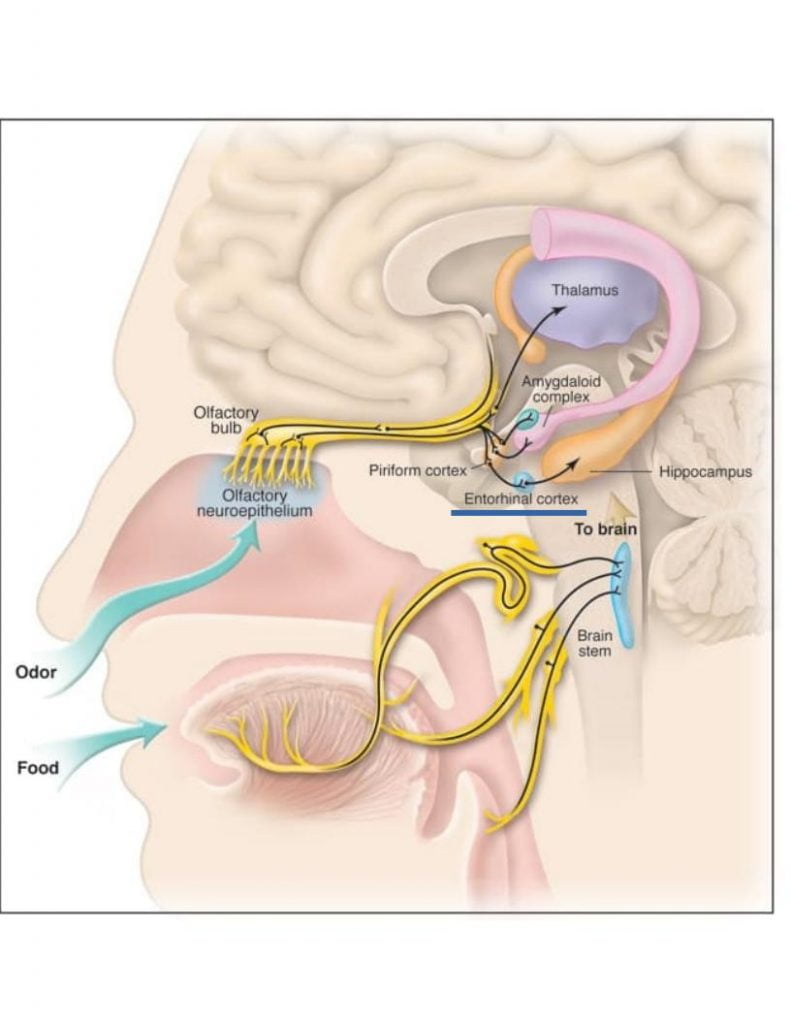

The sense of smell, known as olfaction, is part of the olfactory system. It is a dual system of detecting odour molecules. The first pathway is through the nose (orthonasal perceptions), and the other is through the mouth (retronasal perceptions).

The molecules responsible for the odour are called odorants, and their aromas are perceived through the olfactory sensors.

The aroma plays a huge factor in forming a flavour profile. Well, over a hundred individual aroma compounds in wine interact to create thousands of potential smells, in some ways making sensory road markers that point to specific wines. The olfactory sense is believed to be responsible for nearly 80 percent of the initial flavour perception.

Aroma’s pathway to the sensory processing center begins with detecting the aroma molecules (bouquet) and sending a signal through the olfactory nerves straight to the brain sensory center (the olfactory bulb), where the contextual smell image is created. From there, the odour messages go to several brain structures that make up the “olfactory cortex.

Retronasal Smell (Olfaction)

Retronasal olfaction is the perception of odours from the oral cavity during eating and drinking. It is often confused as being part of the taste. After a sip of wine, the air is taken in and circulated with wine in the mouth. The next step is to breathe out while the lips are closed; the resulting air moves up the nasal cavity, merging with the orthonasal smell and adding additional aromas to the already-formed contextual image in the olfactory bulb.

Along the way, these inputs connect to the Amygdala and the Hypothalamus, invoking emotional responses and memory associations.

Taste

The primary purpose of taste is to protect us from potentially harmful food or drinks. Think of it as a gatekeeper; sweet might be good, but bitter or sour may signal spoiled food.

The tongue is the main organ responsible for taste. It contains taste receptors that identify non-volatile chemicals in foods and beverages. When our taste buds are exposed to wine, it triggers a chemical reaction with the taste receptor cells located on the taste buds in the oral cavity, mainly on the tongue. The detected information is sent to the brain, allowing us to identify the wine taste qualities.

There are five known tastes and mouthfeel sensations related to wine.

- Sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami

- Sensations

- Astringency – tannins in tea or red wine can cause this sensation, usually as roughness on the tongue. I am primarily experienced in red wines.

- Spiciness—Certain compounds in the wine (Syrah, Grenache, Malbec) stimulate receptors in our mouth called Polymodal Nociceptors, which detect the heat and not the spice compounds.

Drinking wine and Aftertaste

The aftertaste is the flavours that linger in the mouth after the wine is spat or swallowed.

The “finish” is important to the wine’s character and quality. Good wines tend to have a long and complex aftertaste instead of a harsh taste or texture, usually due to a high level of tannin or acid.

All the senses mentioned above combine their sensory images in the cortex areas (conscious brain area) to create the image of wine flavour. That’s not yet the complete flavour image; one more thing is missing: the emotional input.

Emotions

Emotional factors affecting the perceived taste of a wine can include aroma-triggered memories, bottle packaging, background noise, surrounding odours, pleasant ambiance, and the present company. These subconsciously processed emotions influence the actual wine’s physical taste.

Suppose one was only after that, the pure taste of wine, doing a blindfolded test, and only focused on the quality of a wine. In that case, the emotional input is not as important as if a person just wanted to have the “perfect” glass of wine with good company.

Understanding how our brain perceives and constructs flavour images shows that there is not much difference between the experts (sommeliers) and the regular folks. We all use the same input and brain processing centers to make sense of the inputs we receive.

From a flavour perceptional point of view, we can all be wine sommeliers if we want to, and that’s one of the significant differences. Becoming a wine sommelier takes time, practice, memory, and love for what you do.

But there is one more critical factor to consider: the ability to describe what we taste, and that’s the language.

I am sure almost everyone has experienced a moment of unique sensory sensation, and as soon as we try to put it in words, the magic disappears; the words sometimes can not fully express how and what we feel.

It doesn’t matter what language we speak; our ability to explain what we feel and perceive is limited to our vocabulary. Wine drinkers, especially, are very familiar with this feeling and unable to describe the aroma as they sense it.

Wine Language

How can you use words to bring alive a smell?

Does the language we use limit us when describing wine flavour?

Professional wine tasters use specific wine descriptive language to describe and evaluate sensory attributes in wine. Communicating wine experiences is essential for sommeliers, merchants, and journalists to connect with guests and consumers, train personnel, evaluate wine and food pairings, and create a vivid sensory image.

One of the most challenging tasks in wine testing is describing the perceived sensation and finding the right words to describe the flavour and relate it to the audience.

According to Emile Peynaud, former Professor Emeritus of the Bordeaux Institute of Oenology,

It is impossible to describe a wine without simplifying and distorting its image” – and issuing warnings of the tendency to error, verbiage, and “unwarranted expressions.

In this subjective area, the relationship between sensation and expression, between the word and the quality it describes, is not as straightforward as it is elsewhere.

Emile Peynaud, The taste of wine book,1983

He also talks about flavour language and our imperfect knowledge of smells and tastes. According to him, the problems are not in the flavour compounds found in grapes and wine but in the lack of vocabulary to describe them and the wine language’s use. The chosen language used by oenologists and wine experts should be based on the intended audience’s knowledge, cultural background, and present set of mind for the sensory image they try to describe to make sense.

Other academics share similar opinions. Experts from the Oenology Faculty at the University of Bordeaux, Brochet, and Dubourdieu suggest that an associative system is used for wine description in their research on descriptive wine language. These sensations are descriptive terms that do not necessarily describe the taste sensations of the wines.

All descriptive language is based on wine protypes and not on individual wines. When a taster is describing a wine flavor, in fact using words to describe similar wines they have tested before, and not necessarily the one particular wine. The descriptive language used is based on previous personal experiences, in effect they analyze based on association of previous subjective taste experiences.

Wine Descriptive Language Supports Cognitive Specificity of Chemical Senses

If you are unsure how to describe the detected wine aromas and struggle to find the “right” descriptive words, this tip might help you accomplish that.

After you taste the wine, start immediately saying any flavour-related words that come to your mind: straw, grass, rain, jam, blueberries, sour, bitter, morning, etc. Many words may or may not even be related to wine, but somewhere among them, you will find words that best describe the flavour you experienced. The whole idea of this process is to try to capture the taste perceptions before they reach the orbitofrontal cortex (the conscious center), where our decisions are influenced by many external factors (audience, reputation, wine rankings, etc.) Clear your mind, pretend it’s only you and the wine in the room.

Over the years, many scientific efforts have been made to categorize wine flavours and compounds, but today’s ultimate sensory taste remains our taste evaluation.

The final aim of any sensory evaluation is straightforward; it all boils down to a simple brain-flavour decision of “Good or not Good.” In that case, we, after all, are not different from the professionals.

Based on one’s language ability to convey sensory perception and wine quality, professionals seem to be in the same boat as regular wine-loving people. There is no advantage here.

What is a sommelier, and what does it take to become one?

The sommelier is a wine waiter, a trained and knowledgeable wine professional, usually working in a restaurant environment. Many professionals also work as sommeliers without formal training, which doesn’t mean they are not knowledgeable about wines even though they have not been through accredited learning.

Are these sommeliers better or worse than the trained ones? It all depends on the individual’s willingness to learn and love their job. As we saw before, the perception of flavour has the same pathways, so if there is an advantage for the certified sommeliers, it is in the broader information learned during their training.

How to Become a Sommelier

The two significant sommelier providers’ certifications are the Court of Master Sommeliers and the Wine & Spirit Education Trust.

The Court of Master Sommeliers (CMS) is the leading educational organization for wine service professionals. Established in 1977, it encourages quality standards for beverage service in hotels and restaurants.

The Wine & Spirit Education Trust (WSET), accredited by the UK government, focuses on developing tasting skills and product knowledge of the world’s significant wines and wine-producing regions. These skills can be applied to understand and evaluate all wines, regardless of region. It is also oriented towards wine enthusiasts who desire to learn about wine and are not interested in technical service.

Both programs have four levels of progressive study. In CMS, a student has to finish the first level before moving to the next; in WSET, one can choose to enroll in any level of 1-3, but the student must demonstrate equivalent wine knowledge.

CMS Levels

Introductory Sommelier Certificate (CMS I)

Certified Sommelier Examination (CMS II)

Advanced Sommelier Certificate (CMS III)

Master Sommelier Diploma (CMS IV) is more than a Master of Wine. It includes theory, tasting, wine, beer, and spirits service. One hundred seventy-two professionals have earned the title of Master Sommelier as part of the Americas chapter since the organization’s inception. Of those, 144 are men and 28 are women. There are 269 professionals worldwide who have received the title of Master Sommelier since the first Master Sommelier Diploma Exam.15

WSET

WSET Level 1 Award in Wines

WSET Level 2 Award in Wines

WSET Level 2 Award in Wines

WSET Level 4 Diploma in Wines – 500 hours of study time, including educator-guided online or classroom study and personal study, over six units ranging from viticulture to the business of wine. Examinations vary by unit.16

Passing all the levels is not an easy task. It takes lots of time, dedication, tasting, and good memories to recall all the aromas and recognize the wine grape varieties and the terroir (the sensory attributes of wine related to the environmental conditions in which the grapes are grown).

As you can see, becoming a sommelier or wine expert can be a daunting task. What differentiates them from the occasional wine drinker is the acquired knowledge, sensory memory, and years of experience and learning.

Does that mean wine experts are way better at flavour discovery than regular Joes? Well, let’s see. So far, we have covered language limitations and brain flavour perception, and we’ve seen that sommeliers and ordinary people have the same sensory pathways. Granted, some experts have an impressive ability to smell, but still, in general, we are all the same.

Okay, the result is 1:1; there is no advantage here. The next factor to consider is experience and wine knowledge, which are advantages to the sommeliers. The result is 2:1 wine experts.

Why do we need sommeliers?

Do we need wine experts if we are that similar in flavour recognition? Theoretically, we don’t need sommeliers; their taste is not better than someone else’s.

But in real life, things are a bit different. People have jobs and families to care for and no time to sit at home and study. They want to go to a restaurant and enjoy good wine and have a great time, and that’s where the wine stewards come in and use their wine education and knowledge to make our choices easier. Suppose one wants to close the gap with the professionals. In that case, they need to practice smelling, naming, and remembering the aromas and flavours encountered in wine and creating their taste preferences.

A structured list of words, such as the Wine wheel and vocabulary used by experts like Robert Parker, can be used as a reference.

Wine Rating Systems

People can use different numerical wine rating systems to search for wine scores and tasting notes. Most wine reviews are aggregated summaries by a few wine critics, and the score reflects their subjective view of the wine quality and taste.

The primary purpose of the rating system is to try to objectify the completely subjective flavour experience and categorize it in some structured, meaningful way so that our brains can make conscious decisions. These ratings are beneficial and primarily used in marketing as structured, objective rankings based on a particular wine’s recommendation.

Consumers can also use these wine systems to compare their tasting experience with the posted wine-tasting notes or increase their wine knowledge.

We must remember that these rankings summarize highly subjective reviews and should be guidelines, not influence our taste experiences. Someone else’s flavour perception already influences us by just being aware of a particular wine’s reputation or ranking. Sometimes, during a tasting in our mind, we might not agree with an expert opinion, but to be part of the group and not look like an amateur, we often agree with the majority’s sensory evaluation.

Understanding that external factors might influence our opinion will help develop and create trust in our palate.

The main goal of being a sommelier?

The sommelier’s craft is similar to bartending: They always look at new products, explore flavours, and constantly learn. That knowledge can sometimes shift the focus from why they got into the wines to learning for the sake of learning, which can hurt sales and customer satisfaction.

Finding the appropriate descriptive words by the wine experts is not a huge problem. They have hundreds of descriptors available, but relating the professional’s language to the rest of society and conveying their sensory experience to the rest of us can sometimes be a challenge.

Suppose the geeky side takes over without even realizing it. In that case, you might hear yourself recommending wines using descriptive words (Chunky Monkey, flabby, foxy, or tight) that sound like a coded speech from a spy movie or going into such details about the terroir (soil moisture, sunny days, vineyard slop inclination) that I bet by the time you finish, the guest will probably order a beer.

Instead, the sommelier can use descriptor words that the guest can associate with and relate to a particular aroma or texture. For instance;

- ANGULAR – high acidity

- BUTTERY – lower acidity, a cream-like texture

- Flabby – no acidity

- Structured – high tannin and acid and is hard to drink

- Tight – not ready to drink

Relating to people is probably the most critical part of being a sommelier or wine expert, as is the choice of not showcasing your knowledge or the superior sensor perception. Empathize with the person in front of you. That’s crucial in the service industry.

Use the acquired wine knowledge to help the guest choose, not show how well-educated you are.

Here are a few simple rules to keep your focus in check on what is essential.

- Agree with a customer. If they want white wine with their steak, try to offer the most suitable one.

- Use the knowledge you have as a tool to provide excellent customer service, not as a way to intimidate and confuse people.

- Think about how people see you as helpful and how you can help them make easier decisions. The guests don’t want to hear the wine lecture and are here to have a good time.

- Ask people what their favourite wines are if you are unsure how they feel about drinking them.

- You can stay in their comfort zone and offer something similar. If they like Cabernet and want to try something similar, maybe the Malbec-to-Malbec-Cabernet blend will do it.

- If they want to be adventurous, offer a wine they’ve never heard of.

- Don’t always offer the most expensive wine; people will appreciate suggestions of better-priced wine with similar characteristics.

I have seen people refusing to make a drink or serve a particular wine because they think the customer is wrong and know better than them what the right wine is.

In the bartending world, the saying, “Don’t make drinks for bartenders,” only serves what you’ve been asked to make.

The same applies to sommeliers: “Don’t treat people like wine connoisseurs,” go along with their preferences and help them enjoy their night out.

Wine and food pairing

Numerous books have been written on wine and food pairing. It is a highly subjective art form, but a few main points might help us offer some suggestions to our guests.

The main goal of pairing is to complement the food and wine and not overpower each other.

There are different approaches to pairing, and here are some ideas on how to do it.

- Understand how the dish was prepared, not just the meat type, but sauces, herbs, and specific ingredients. Simplify dishes to their main ingredients. Then, look at the wine flavour profile and see if similar flavours are part of it.

If someone ordered lobster with Mâitre d’Hôtel Butter, a white wine with a buttery profile like Chardonnay might be suitable.

- The body of the wine should match the weight of the food—for example, a light-bodied wine with a light dish.

- Red wine counters the fat content in red wines.

- White wine with light meat.

- Fruity wines with fruity dishes.

- Sweater wine (Riesling) with a salty dish.

- Spicy food with sweeter wine (Gewürztraminer).

- For gaming birds, use pinot noir.

- Use local wines to pair with regional dishes.

Wine Regions

“Old World” vs. “New World”

“Old World” wines refer to wines from countries with a long history of winemaking – France, Italy, Spain, Germany, Portugal, and Parts of the Mediterranean. These are the areas where modern winemaking traditions first originated.

Generally, they are labelled based on the region or place, the unique characteristics of the soil, and the climate(terroir – distinctive characteristics of the soil and climate). They usually have lower alcohol content and higher acidity.

“New World” (as the name suggests) describes newer wine-producing regions that implemented the winemaking techniques from the Old World, such as North and South America, Australia, and New Zealand.

These regions tend to have hotter climates and generally use different labelling methods; they tend to use grapes rather than regions on labels for recognition.

Major wine regions and the grapes they are best known for:

| France | Merlot, Grenache, , Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon, Carignan, Chardonnay, Cabernet Franc, Pinot Noir, Gamay, Sauvignon Blanc, Gewürztraminer, Semillon |

| Italy | Sangiovese, Montepulciano, Merlot, Trebbiano Toscano, Nero d’Avola, Barbera, Pinot Grigio, Prosecco, Nebbiolo, Muscat – more than 200 varieties around the world. |

| Spain | Tempranillo, Airén, Garnacha, Monastrell, Bobal, Pedro Ximenez, Palomino |

| Germany | Riesling, Müller-Thurgau, Gewürztraminer |

| USA | Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Zinfandel, Sauvignon Blanc |

| Australia | Shiraz (Syrah), Chardonnay |

| Argentina | Malbec, Bonarda, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon |

| Chile | Malbec, Bonarda, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon |

| South Africa | Chenin Blanc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinotage, Chardonnay |

| China | Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Carménère, Marselan |

If we look at the history of winemaking countries, some are classified as part of the “New World,” and wines (China and Russia) have traditions dating back thousands of years.

The volume of wine produced in European wine-producing countries in 2020. (in a million hectoliters)

Grapes, wine cultivars, production, tasting, wine ratings, and confusing language can create overwhelming information and cause indecision and frustration (did I buy the right wine?), feelings of inferiority, and lack of self-esteem (I can’t afford it). That usually leads to relying on someone else to tell you what wine is good for you.

A simple approach might be to use the ratings and sommeliers’ advice as guidelines and learn to trust your palate.

Let’s not forget one simple fact: we all have the same sensory pathways at the end of the day, and flavour evaluation is deeply personal.

Footnotes

- https://www.fifthsense.org.uk/

- https://neurosciencenews.com/covid-smell-loss-20007/

- https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/providence/name/trygg-engen-obituary?id=15915130

- Neurogastrony, Gordon M. Shepard, p.137

- https://academic.oup.com/chemse/article/30/8/643/398749

- http://www.daysyn.com/morrot.pdf

- https://www.mastersommeliers.org/about

- https://www.wsetglobal.com/

- https://www.fifthsense.org.uk/

- https://neurosciencenews.com/covid-smell-loss-20007/

- https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/providence/name/trygg-engen-obituary?id=15915130

- Neurogastrony, Gordon M. Shepard, p.137

- https://academic.oup.com/chemse/article/30/8/643/398749

- http://www.daysyn.com/morrot.pdf

- https://www.mastersommeliers.org/about

- https://www.wsetglobal.com/